Nikkō’s a Real Trip

Matías Ariel Chiappe Ippolito

translated by Andrea Rosenberg

日々旅にして旅を栖とす。

(松尾芭蕉)

“Every day is a journey, and the journey itself is home.”

–Matsuo Bashō, tr. Sam Hamill

I’d been told I should get in touch with Hideki, whom everybody calls “the sensei.” I thought I was prepared for my visit to the city of Nikkō—I’d asked a number of people and looked at a bunch of websites; I’d even acquired a tourism pamphlet about Tochigi Prefecture that I hadn’t gotten a chance to read yet. I knew about the surrounding area: Kegon Falls, the Shinkyo Bridge, Mount Nantai. I knew that the main attraction was the Rinnoji Temple and the shrines of Futarasan and Toshogu, the latter of which houses the tomb of Ieyasu Tokugawa, the first shogun of the Edo period. I knew I was about to enter an ancient, magical place whose buildings were decorated with carvings of dragons and cats and, most famous of all, one with three monkeys covering their mouth, ears, and eyes, respectively. A place suspended in mist and crisscrossed by a million lantern-lined paths.

Each of these elements has a story. One of the lanterns, for example, is known as 化灯籠 (Bake-Doro), the Ghost Lantern. This lantern is famous because, thanks to its particular design and the properties of the materials it’s made from, the shadows it casts are unusually dense. The samurai of centuries past, believing that the lantern was invoking ghosts and spirits, would attack the shadows, never making contact with those illusory menaces. You can still see the marks of their swords, born of paranoia or a bad trip, on the lantern’s lattice-work. People were so terrified of the lantern that even today it’s lit only once a year, from April 13 to 17, during the Yayoi Festival, when the place is packed with people who could come to one’s aid in case of a spectral assault.

“You’re into that crap?” Hideki asked me when I said I was going there next, describing my intention to follow in Matsuo Bashō’s footsteps on a trip that would take me through all of Japan. I stared at him for a second. Then I looked down. I felt like a tourist, a dupe; I sensed that the man before me knew a great deal and carped about the same things Ariel Rodó had objected to in Rubén Darío’s imitations of Loti: the novelty of appearances; frivolity; easy, amusing puerilities. “I guess,” I said, like an idiot. He laughed and told me all those things were only interesting on the surface. “So what’s the best thing in Tochigi, then?” I asked. Telling me to hang on, he got up from the futon, went over to a little bookcase to fetch a book, and opened it in the middle. He showed me the image, which filled the entire page.

“Tochigi is the land of Japanese marijuana,” he said, showing me other photos from the book: hemp fields, ukiyo-e woodblock prints of weed, lacquered smoking pipes in every shape and color. Then he added, “It’s grown other places too, like Nagano and Okinawa, but nothing as potent as what we have here.” He continued in the tone of somebody giving an academic talk: the material produced from the marijuana plant (commonly known as hemp, he clarified) was used in countless ways on the Japanese archipelago starting in the Jōmon period, a thousand years before Christ. Later it was used in the manufacture of clothing and baskets, to make writing paper during the Heian period, to tie coins together in the years of the feudal lords, in performing dohyō-iri (when a sumo wrestler cleans the combat area wearing a hemp rope around his waist), and, because of its durability, for soldiers’ hats during World War II. In addition, cannabis has long been a symbol of purity in Japan’s native religion, Shintoism, and is used for rituals and ceremonial clothing.

“But in 1948 production was outlawed during the US occupation of Japan.” Apparently, General Douglas MacArthur thought marijuana was closely linked to communism, politica non grata after the war. It was also associated with the black musicians who’d ruined real American jazz. As his homeland was wont to do, he established a prohibition in Japanese territory. “Yukio Funai, the author of this book, says it was because of military factors—a way of reducing Japanese military power, which had been running a vibrant, profitable industry.” Whatever the case, that prohibition remains in place today. Politicians have even been reluctant to loosen (I mean, update) the penalties or even consider allowing medicinal marijuana, Hideki added. Again I stared at him in silence. On this topic, it seemed, Latin America and Asia, or at least Japan, shared a history of imposed Yankee hypocrisies.

At any rate, Tochigi became the epicenter of a countercultural resistance, reclaiming the country’s long tradition of cannabis use. “So that lantern thing doesn’t have anything to do with the lantern’s design or materials. The samurai, honoring customs from our most ancient traditions, were high as a kite, and they’d just go whacking away at the metal pole with their swords.” The image of a Rastafarian samurai flitted through my mind. This meant that one of the most important centers of so-called “Japanese culture” was actually a pot paradise. “Did you see the movie The Beach?” “Of course, I’m obsessed with the ’90s.” “Well, kind of like that, but with Japanese scenery.” How many other cultures could explain themselves through their use of sacred psychotropic plants? I recalled that Albert Hofmann and Robert Wassan proposed something similar about Greek culture when they analyzed the concoction consumed during the ritual to the goddess Demeter; they concluded that the mixture of wheat and barley was an excellent medium for the fungus Claviceps purpurea, from which a precursor of LSD can be derived.

“This is all I have left from then . . .” Hideki said, opening a little box decorated with an image of a smoking geisha. While loading a pipe, he asked me if I’d ever thought about the connections between marijuana and poets like Bashō, who “were actually the hippies of their time,” he noted. A counterculture that resisted first the imperial aristocracy and then the military elite. “That’s why they had such an impact on the beatniks.” Haiku poets as forerunners of stoned hippies? It was true that the beatniks had taken Bashō and his disciples as models. Not just in terms of pilgrimage, escape, and vanishing lines, but also by adopting Zen Buddhism as the core of their philosophical project. “Exactly,” Hideki said, bringing the flame up to his face.

One poet who exemplifies these unexpected connections was Dom Sylvester Houédard, a Benedictine monk at Prinknash Abbey, who translated the Bible while exchanging letters with Ginsberg, Burroughs, and others. Like the beatniks (or, rather, like Saint John of the Cross and Sor Juana Inés), Houédard was seeking some kind of mystic revelation, which he found both in Catholicism and in haiku. Unlike the beat poets, however, he chose to write visual poetry, so-called “concrete poetry,” and especially calligrams. In fact, he wrote a number of pieces of literary criticism, each of them in a different calligraphy. He also translated Bashō’s famous haiku about a frog:

frog

pond

plop

The original (古池や蛙飛びこむ水の音 Furu ike ya kawazu tobikomu mizu no oto, which can be translated literally as “Old pond / a frog leaps / sound of water”) has been the object of hundreds of versions, with greater and lesser degrees of embellishment: “The old pond / a frog leaps in, / and a splash” (Makoto Ueda); “Un vieil étang / une grenouille plonge / le bruit de l’eau” (Joan Titus-Carmel); “Un viejo estanque / salta una rana, ¡zas! / chapaleteo” (Paz and Hayashiya). But I think Bashō would have liked Houédard’s (even more) minimalist version. Or at least found it amusing. Maybe it would have confirmed for him that there are coincidences in this world, in this universe. After all, one of his contemporaries had experienced a similar revelation. Bashō observed a frog jumping into a pond and—splash!—a moment of mystical enlightenment. Meanwhile, in England, an apple fell on Newton’s head and—thump!—a moment of rational enlightenment.

Hideki reached out and handed me what from that moment on I began to think of as a basic and even necessary element of “Japanese culture”—if such a thing exists, if it is necessary to qualify it in national terms. Then he stretched from the futon without getting up and moved his fingers on the touchpad of his computer. Scroll up, scroll down, and, with a little tap like a leaping frog, he selected a song from a playlist. “These guys do a mix of folk, ska, and reggae, all in the Ainu language spoken by that ethnic community in Hokkaido.” I looked over and managed to see the name of the band: Oki Dub Ainu. Hideki told me about other similar groups: the rapper Oni and his band Still Ichimaya; the singer Likkle Mai; Cicala Mvta, who’d done a cover of Víctor Jara’s “El derecho de vivir en paz.” It was a brief, fascinating trip through stoner music in present-day Japan.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0ByiXt0TUr0&list=PLN8jn1rpcIHCCDsH3_Tg5rO2_4x3-_JI1

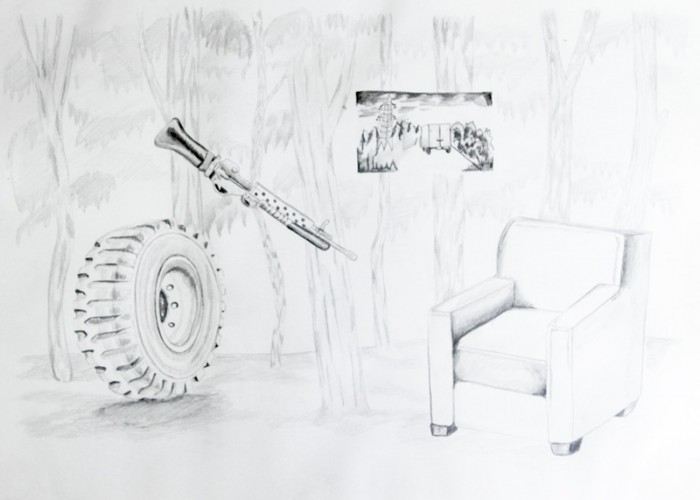

After a while, I couldn’t get my eyes to focus anymore. Hideki was telling me about the trees around the Nikkō shrine. “Out in those woods, I had the best . . . the most intense trip of my life.” He told me he’d gotten so high on a joint of Toshigi marijuana that he didn’t even know where he was. At one point he got lost in the music in his headphones and started wandering aimlessly through the trees, along a creek, and past some waterfalls—walking for two, three, who knows how many hours—and came to a clearing with a cabin, through whose windows he thought he spied naked bodies in bizarre sexual positions; he kept going and ended up in a little town right out of the American Old West, with horses and barrels and the inevitable sign reading “Saloon”; and then he got the feeling like somebody was after him and took off running, and only then noticed that there were some ninjas with swords behind him. “ほんとだ!” he added. He said he managed to escape that nightmare—he doesn’t know how, but he reached a train station, where he boarded a train and slept the whole way back. “Like I say . . . the most potent ganja in Japan.” His story seemed so wild that I never for an instant doubted it was true.

We said goodbye and he told me, “Have a good time in Nikkō. Next May we’ll go to the legalization march together.” I left. In the train on the way back, I rummaged in my backpack and found the same items as always: my collapsible umbrella, that Pynchon novel I can’t seem to finish, the kanji flashcards that by now I think are going to be with me for the rest of my days, as if they were prayer cards or some kind of talisman. Way down at the bottom, I came across the tourism pamphlet. I opened it. There, among other things, I found information on the Kinugawa Sex Museum; the Old West–themed amusement park; the ancient village of Edo, where they still do ninja shows . . . Even all about a “Marijuana Museum.” “Tochigi, Japan’s most amazing prefecture,” the pamphlet declared. I thought back to the pyramids at Chichén Itzá, swarming with vendors; Notre-Dame Cathedral, where they sell souvenirs during mass; the section of the Great Wall of China where they installed a slide for visitors to ride down on little carts. I sat staring straight ahead, eager to get home. When I left Koenji Station, the wind blew a ticket out of a woman’s hand and down a storm drain. It was a moment of revelation, a trip: I was suddenly filled with the words I’ve just written here.

* * *

Bibliography

船井幸雄 [Funai Yukio].『悪法! ! 「大麻取締法」の真実』[¡Damn law! The truth about the marijuana prohibition in Japan]. Tokyo: Business-sha, 2012.

Mitchell, Jon. “Cannabis: The Fabric of Japan.” The Japan Times. Accessed 21 Nov. 2016.

長吉 秀夫 [Nagayoshi Hideo].『大麻入門』[Introduction to marijuana]. Tokyo: Gentosha, 2009.

* * *

Images courtesy of the author.

[ + bar ]

DARK (an overture)

Edgardo Cozarinsky translated by Cayley Taylor

It starts, always, in the temples, an almost imperceptible throbbing at first, and in the precise moment he acknowledges it, that pulsing starts... Read More »

Three Snapshots on the Way Down

Edgardo Cozarinsky translated by the author

1. “Il vecchio non trova pace”

What’s that you’re saying, I am about to snap at the barman with my coldest voice... Read More »

Edipo [buenos aires]

Milton Läufer translated by Heather Cleary

It’s true: Edipo is an ugly bookstore. And yet, though this may seem like a contradiction, its most notable... Read More »

Thibault de Montaigu

Certains sans doute estimeront que cet ouvrage manque de rigueur et qu’on ne peut décemment rédiger une enquête criminelle en restant confortablement installé chez soi... Read More »

![Edipo [buenos aires]](http://www.buenosairesreview.org/wp-content/uploads/Screen-Shot-2013-04-20-at-11.16.56-PM-700x500.png)

sending...

sending...