On Mario Bellatin

Edmundo Paz Soldán

translated by Sarah Bruni

Fifteen years ago or so, I traveled to Lima in search of a shaman who would free me from the ghost of a dead friend. The friend had killed himself, and his ghost, or what I thought was his ghost, appeared to me every night. Lima, they said, was the solution, so I went. The shaman was dressed in black, wore military boots, was bald and missing his right arm. His name was Mario Bellatin and he went everywhere with his dogs. He was also a writer. He told me he wrote novels, though genres were actually rather blurred for him. He wanted to reach a point where he would be free to just to write books. In the first therapy session he asked me to write for an hour. About what, I asked. Anything you want, like when you were a child. So I did, somewhat nervous because I wasn’t used to such informality. I admired Vargas Llosa—that meticulous structure, that narrative architecture. Mario laughed when I mentioned Vargas Llosa to him. He told me that writing was intuition and gave me some of his books. Beauty Salon impressed me, Flowers and The Szechuan School of Human Pain startled me, and Blind Poet left me cold. I asked him about my dead friend. In reply, Mario started to spin like a dervish. He belonged to the Sufi religion, he told me, and this had taught him that I should not be afraid of my friend. Instead, I should enjoy him. The dead are alive and remain with us, he said. They live in another reality, perhaps more interesting than this one. I left Lima with a certain peace of mind; although the friend didn’t stop appearing, I already knew what to do with him, at least, that’s what I thought. Five years later I traveled to Mexico, and in the subway I encountered a man dressed in black, wearing military boots, bald, and missing an arm. Mario, I whispered. He told me that by pure coincidence his name was Mario, but he didn’t know me. His last name, also by pure coincidence, was Bellatin. He sold his books in front of the subway. They were handmade books, in good condition. He wanted to write a hundred books, and if he published a thousand of each, he would sell a hundred thousand. I bought several from him, still surprised by the meeting, sure that he was who I said even if he denied it. At home, I read books I didn’t understand, with titles that mentioned dead hares and great glasswork, books written in an impenetrable style that denied me access. Even so, I went back to the subway the next day to say hello. I didn’t find him. I thought that maybe Mario Bellatin had died long ago and I had run into his ghost. A little while later, in Ithaca, where I live, the visions began. One day, in the mall, Bellatin started walking with me and stole a baseball hat from an Old Navy store. Another day he gave a presentation to my students on Beauty Salon, during which he never opened his mouth. The students listened entranced to a recording of Mario on the autobiographical origins of Beauty Salon. To talk about Shiki Nagaoka: A Nose for Fiction, he showed us a ten-minute video in which he goes on about Rulfo, José María Arguedas, and Prince while his dogs run around the house. Bellatin stopped appearing, but his books continue to. The most impressive of all is called The Uruguayan Book of the Dead (published by Sexto Piso). “The truly unique images come from the intuitive,” says the narrator of this flawless book, whose name is Mario Bellatin, although this intuition is, of course, also governed by a meticulous structure, an impressive narrative architecture. Which Mario is the narrator? It doesn’t matter anymore. I now understand that, starting with his years in Lima, he has been building a phantom reality from his apparently iniquitous practice. A space where the rules are different. So different that they made possible a moment in which, at my age, I would set out after a Mario Bellatin who wandered through the subway stations of Mexico City selling, one by one, the books that—irony of ironies—are slowly turning him into one of those indispensible beings that will never die.

* *

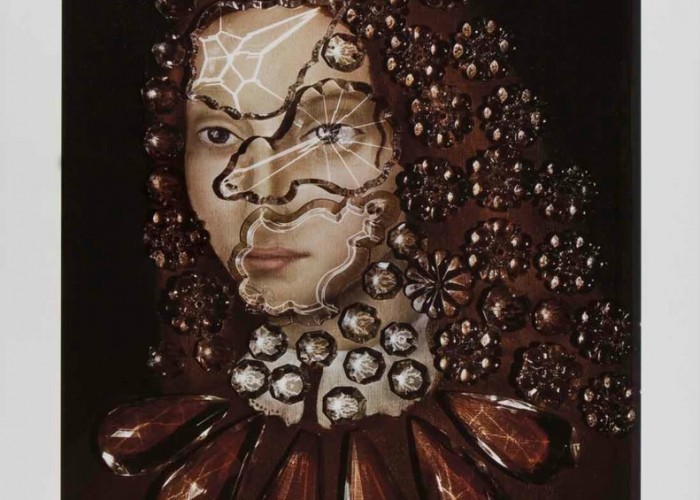

Image: Sebastián Freire

[ + bar ]

Natanael’s Notebook

Veronica Stigger translated by Ramon Stern and Chris Meade

Opalka entered the small room in his son Natanael’s house and walked to the window, under which was... Read More »

Knocking on Keret’s Door

Masha Kisel

In Etgar Keret’s Suddenly, a Knock on the Door (2010), thirty-five humorously unexpected plots develop with the predictable timing of... Read More »

Ishion Hutchinson

A GIRL AT CHRISTMAS

The choir that cannot die. Fish and fennel. Snow. Christmas tree, clover and pomegranate.

For all she’s gladdened: milk which is love dreaming in one hand; clefts of clementine stain

the other.... Read More »

The Pizarro Sisters

Juan Álvarez translated by Heather Cleary

“What,” I said. That was how I answered the phone then. It was a forceful what—scrappy, combative. But combative isn’t quite the word, because... Read More »

sending...

sending...