The Amazing Argentine [excerpt]

John Foster Fraser

Lucas Mertehikian

translated by Jennifer Croft

In 1899, Scottish writer John Foster Fraser (1868-1936) made a name for himself in Great Britain with his book Round the World on a Wheel, the result of a bicycle trip made with two friends across over ten thousand miles of Europe, Asia and the United States. Unlike other books dedicated to travel, Foster Fraser’s book was not “about anthropology or biology or archaeology.” He made no claims to studying the places he went—only claims to fame: “We took this trip round the world on bicycles because we are more or less conceited, like to be talked about, and see our names in the newspapers,” he states in the preface.

And it worked: over the course of the next few decades, Foster Fraser traveled to and wrote about young countries like Canada (Canada As It Is) and Australia (Australia: The Making of a Nation), as well as histories with long and storied traditions, such as Russia (Red Russia) and the nations of northern Africa (The Land of Veiled Women). “Sir John, who was born in Edinburgh, spent almost the whole of his adult life in search of variety,” wrote The Glasgow Herald in his obituary, from June 8, 1936.

It may well have been this same search that led Foster Fraser to Argentina, where, in 1914, he wrote his second-to-last book: The Amazing Argentine: A New Land of Enterprise. Variety, after all, was already in the ethnic composition of his fellow passengers on the ship to Buenos Aires: wealthy Argentines returning from Europe, poor Spanish and Italian immigrants, English businessmen. “South America is not the land of the future. It is the land of to-day,” he writes. The trails blazed by European travelers in the first half of the nineteenth century in the exploration of fields and mines in the Andes had fallen into disuse—but there were now new paths.

Upon his arrival, Foster Fraser encountered a city in which an accelerated capitalist rhythm coexisted alongside archaic gender biases, something Beatriz Sarlo has described as part of Buenos Aires peripheral modernity. Perhaps his voyages around Australia and the Middle East had prepared him for his trip to Buenos Aires, a city whose contradictions he found, as he will note below, strangely fascinating.

Some Aspects of Buenos Aires

John Foster Fraser

The Argentines call their city of Buenos Aires the Paris of the southern hemisphere. It has a population nearing a million and a half, which is greater than that of any other town below the line of the Equator. The people promise that in time it will overtake London.

You insult an Argentine if you mix him up with Chilians, Brazilians, and other South Americans. He does not thank you for being reminded his father sailed from Italy, or his grandfather from Spain. He has no affection for any old land from which his sires came. The beginning of the world for Argentina was in May, 1810, when the Republic was set up.

He has no pride of historic race. When he makes money and visits Europe it is not to find the ancestral home in Spain or Italy. It is to have a good time in Paris. When he takes his family to Paris it is not to spend three, five, or six months. It is to spend three, five, or six hundred thousand pesos —and the value of a peso is one shilling and eightpence. When the pesos have flown he returns to Argentina and makes more.

The Argentines are a dignified people. They accept the English because in round figures five hundred millions of British capital in gold have aided in developing the country. They dislike the citizen of the United States because the big brother Republic of the north patronises them, and they need nobody’s help. They have a contempt for all other Latins beneath the Isthmus of Panama, particularly the Brazilians. They are conscious of their own qualities.

And the visitor blinks, and rubs his eyes, and admits the wonders of Argentina. If his acquaintance with geography is casual he has shrugged his shoulders at South American Republics, where they have revolutions every six weeks, and where tawny Spaniards in quaint costumes drive mules and die from difference of opinion with other Spaniards.

Then he goes to “BA” —the familiar description of Buenos Aires— and he finds he has landed in a rampantly modem American-cum-European city. There is none of the sloth of the Southern, no checking of business between noon and three to pass in siestas.

It is a busy city. The port is thronged with shipping, mostly British. High-shouldered elevators stick out long tongues, and streams of wheat, grown on the plains of the interior, pour food for Europe into the holds. Trucks of cattle grunt through the noisy railway yards. There are huge killing establishments, and animals go to their death by the many thousand every day with a celerity which would awaken a Chicagoan. There are mighty avenues of chilled and frozen meat. Labour-saving machinery carries it on board the steamers which hasten across the Atlantic, carrying cheap beef to the London and Liverpool markets. Commerce is conducted on the latest scientific lines. The North Americans have nobbled the meat trade, and the Jews have control of the wheat market.

Buenos Aires is the mart where the produce of the rich back-lands is bartered. It levies a heavy toll. The most imposing business buildings are the banks —national banks, British, German, French, Spanish, and Italian banks. In and about Reconquista are these banks, ever busy. Near by are the rival shipping offices, a glut of them. The offices of the great railway companies are enormous. Widespreading premises exhibit the latest and best agricultural machinery that Lincolnshire and Illinois can produce. There is the hustle of commerce. The streets are as narrow and as crowded and as vital as within the City of London. There is earnestness about the men.

The Argentine is sombre in manner. He dresses in conventional black. A light waistcoat, a gay tie or fancy socks, is bad form. You cannot tell the difference between a millionaire and one of his clerks, except that the former has an expensive motor-car and the latter hires a taxi or a victoria, or travels by electric tramcar. At every corner you see evidence of prosperity, of successful money-making. And money speaks in BA as loudly as it does in New York.

Folk of the Saxon breed tend to scoff at the decadence of the Latin race. But there is something revivifying in the transplanting of a people. We have evidence in our own colonies. The man of Spanish descent in the Argentine is not always the spry fellow he thinks himself; but he has dropped the cloak of sluggishness which enwraps Spain. He is often rich; he lives in a gorgeous residence; his extravagances are beyond those of a Russian archduke. He is polite and hospitable.

But the wealthy Spanish Argentine is not the creator of his own wealth. I heard of only one case of a Spanish Argentine owing his great fortune to commercial enterprise. The fortunes of most of these Argentines come from land. Their grandfathers got immense areas by the easiest means. Properties were so enormous that extent was not reckoned in acres, or even square miles, but by leagues. But a hundred leagues, however good for cattle or sheep, or wheat growing —what was its value a couple of hundred miles from a port? Then came British railways. They pierced the prairies. The land bounded in value, tenfold, a thousandfold. Other people came in; first shrewd Scotsmen; then industrious Italians; then Englishmen bent on becoming estancieros. Their children are Argentines. But the mighty fortunes are mostly in the possession of the early Argentines —those who were settled fifty and more years ago. They have sat still and seen their land blossom in value. They pay no income tax; there is no tax on unearned increment. Mr. Lloyd George was once in the Argentine, associated with a land development company. That, however, is another story.

Hundreds of thousands of immigrants pour into the Republic every year. They come from every land on earth. Mostly do they come from Spain and Italy. Italy provides the greatest number, and splendid colonists they are. Though the language will always be Spanish, the race is rapidly becoming Italianised. There is a commingling of the sterner stuff from Europe. So in this rich land —rivalling Canada and Australia in productiveness— there is being blended a new people, keen, alert, successful, ostentatious, pagan —a people that has a destiny and knows it.

The Argentines are town proud. You are not in Buenos Aires a couple of days before you are bombarded with the inquiry, “Don’t you think this is a beautiful city?”. It is not that; but it is an interesting city.

In the oldest quarters the streets are narrow, after the Spanish style. So narrow are they that, with electric cars jingling along them, vehicles are allowed to journey only one way. To reach a shop by carriage it is sometimes necessary, to drive along three and a half sides of a block of buildings. Funny little policemen, brown faced, blue clad, and with white gaiters and white wands, direct the traffic. In the Florida —the Bond Street of BA— all wheeled traffic is prohibited between the hours of four and seven in the afternoon, so that shoppers may have an easier way.

Most of the streets are called after Argentine provinces, or neighbouring republics, or national heroes, or some politician or rich man who can influence the authorities. When a popular man has lost his popularity the remnant of his fame is obliterated by the street called after him being named after someone else. It is as though the Government at home decided to change Victoria Street, Westminster, into the Avenida Asquith, with the prospect of its being altered later on to the Calle Bonar Law.

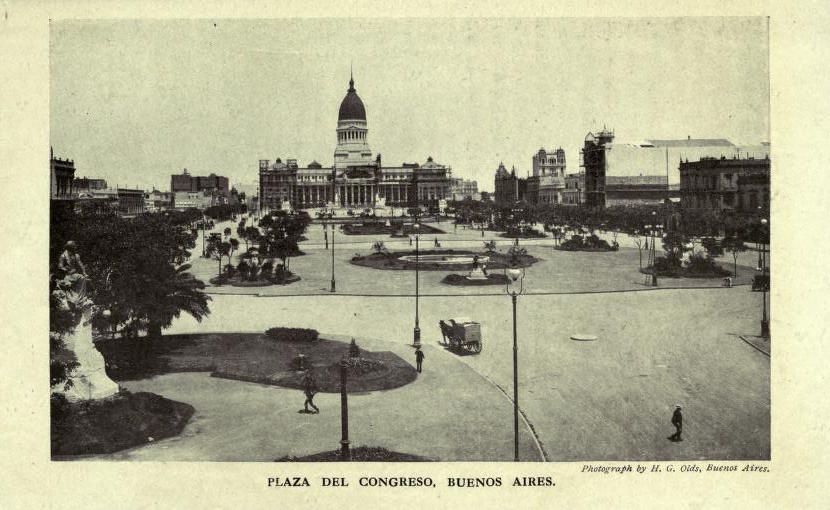

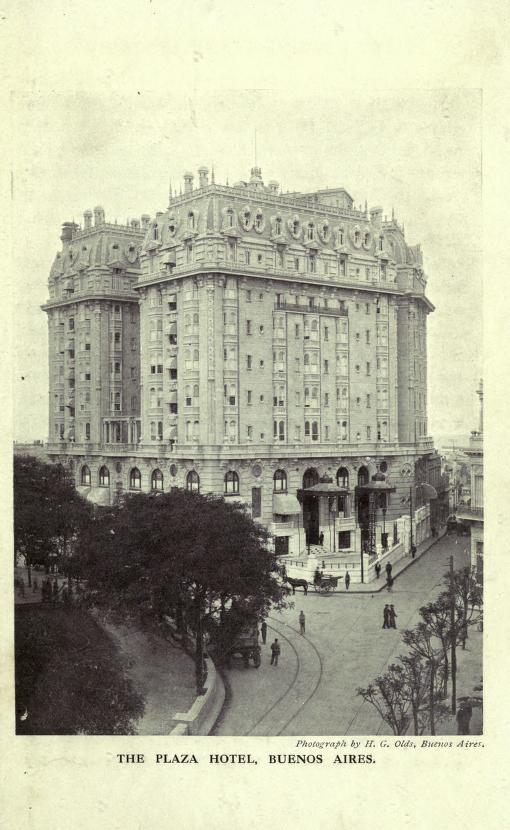

Wide plazas decorate the city. Vegetation is luxuriant, and statues are numerous. The Plaza Mayo is not called after an Irish peer, but after the month of May, 1810. The shops are as big as those in London. Argentina manufactures practically nothing, and all the lovely things have to be imported from Europe. The hotels are imitations of those in Paris. The restaurants are on a par with the best we have in London. A Viennese band plays whilst you have Russian caviare and the waiter is asking your choice in champagne. But everything is expensive. A man needs three times the salary in Buenos Aires to live the same way he would live in London. If you calculate exchange rates you go mad. It is best to count the peso (1s 8d) as a shilling, and then remember that you are spending your shilling in South America, where things are dear. You can get a modest luncheon for 10s; but you will pay 2s for a bottle of beer, and 8s 6d for a cigar worth smoking.

Yet nobody minds. Immense sums are being spent on improving the city. It is built on the American T-square plan. But it is to be subjected to the plan of Haussmann, with great tree-girt avenues radiating diagonally from the Plaza Mayo. An underground railway, honeycombing beneath the town, is in rapid construction. The railways have a great suburban traffic, and are being electrified. There are British colonies at Belgrano and Hurlingham, and you have a choice of three golf courses. In the summer months —December, January, and February— there is river life on the Tigre, the Thames of the Argentine. A charming spot is Palermo, a combination of Hyde Park and the Bois de Boulogne —open sweeps and charming trees, a double boulevard with statues and commemorative marbles in the middle, well-cared-for gardens, radiant flowers and the band playing.

A drive through Palermo at the fashionable hour causes one to gasp at the thought that one is six thousand miles from Europe. Nowhere in the world have I seen such a display of expensive motor-cars, thousands of them. Ostentation is one of the stars of life in the Argentine. Appearances count for everything. You must have a motor-car, even though you have not the money to pay for it, and you owe the landlord of your flat a year’s rent. The ladies are exquisitely gowned, but they have not the vivacity of the French women nor their daring in dress. There is a demureness, a restraint which reminds one that the atmosphere of far-away Castile is still upon them.

On Sundays and Thursdays there are races at Palermo. The price Argentines pay for horseflesh has become a proverb. It is a good race-course. We have nothing in England, neither at Epsom, Ascot, nor Goodwood, so magnificent as the grand stand. It is a glorified royal box. The restaurant is like the Ritz dining-room. Everybody dresses as they would at Ascot. There are no bookmakers. The totalisator is used. Betting is officially conducted by the Jockey Club, and there is constant announcement of the amount of money put on the horses. Those who have backed the winners share the spoil, less ten per cent. As this ten per cent, is deducted from the total amount put on each race, the income of the Jockey Club runs into hundreds of thousands of pounds. So the Club maintains a good racecourse, offers capital prizes, has a house in BA —undoubtedly the most palatial club-house in the southern world— and distributes the remainder amongst the hospitals. The income of the Jockey Club is so large it is really embarrassing. The members are proceeding to build an Aladdin’s palace of super-gorgeousness.

But at the races at Palermo I noticed that no ladies attended, except in the members’ enclosure. Even there they did not mingle with the men-folk. There was no mirth, such as we are used to in Europe. They kept themselves to little groups. Moving from wonder to wonder, I was present at a gala performance at the Colon Theatre. I have seen all the great theatres in the world, and this is the loveliest —a harmony of rose and gold. The audience was as fashionably dressed as at the opera in London, though I missed the dazzling display of diamonds which had been promised. Most of the audience were ladies; there were boxes of them, and most of the men were in the stalls. There was one gallery reserved for women.

I began to discern a strange Orientalism in the relations between the sexes. The Argentine women are amongst the best mothers in the world. But there is practically none of the good fellowship between young fellows and young girls which is so happy a feature of our English life. For a man and a woman to take a walk together would shock the proprieties. There are brilliant receptions, but dinner parties, as we know them, are rare. An Argentine seldom introduces a friend to his wife. Except amongst the poorest a woman scarcely ever goes into the streets alone. If she does she runs risk of being insulted. There are Argentines, who would be offended if refused the name of gentlemen, who think it excellent sport to walk in the Florida in the evening and mutter obscenities to every unprotected woman who passes. Buenos Aires is the most immoral city in the world. So the Argentine guards his women-folk from contact with other men. His attitude is a relic of the days when the Moors had possession of Spain.

I have called Buenos Aires a pagan city. So it is. The men are frankly irreligious. In conversation I have been told of the tolerance to all religions. What is really meant is indifference to any religion.

Money-making and flamboyant display —these are the gods which are worshipped. The houses in the wealthier districts are exotic in architecture. I remember driving along the Avenida Alvear, a street of palaces, reminiscent of the Grand Canal at Venice if it were a roadway. But the fine stone blocks are nothing but stucco. The ornamentation, the floral decorations, are not carved stone; they are stucco. Imitation, pretense, showiness, the flaunting of wealth, are everywhere.

Yet this city, which has grown in a generation on the muddy flats by the side of the muddy Parana River, has something that is weird in its fascination.

from The Amazing Argentine. A New Land of Enterprise. London, Cassell and Company, 1914.

[ + bar ]

The Mothers of Gustave Flaubert, Marcel Proust, and Jorge Luis Borges Meet in Heaven

Mary Gordon

An angel in a golden robe escorts the last of three ladies of a certain age into a well-appointed sitting room. It is tenderly lit; there... Read More »

Your Lying Cheater’s Heart

Carmen María Machado

Junot Díaz’s This is How You Lose Her as a Confessional Text

The confessional text—either an author baring his own soul, or a... Read More »

John Freeman

THE HEAT

At night as the heat’s warble strummed to a ticking silence, and the crabgrass turned blue then green then black, the branches above would relax and gently pluck my window-screen, like the dark-haired woman who, years... Read More »

Primavera – Fall 2013: Tongue Ties

This first quarterly issue of the Buenos Aires Review boasts new literary works from a variety of tongues—French, Galician, German, Portuguese, Russian, and a touch of Hungarian accompany... Read More »

sending...

sending...